A Century of Oregon Eating, 1880 – 1980

This post is an edited version of a talk given June 24, 2014, at McMenamin’s Edgefield, Troutdale, for the Oregon Encyclopedia, titled Your Grandmother’s Cook Book: A Century of Oregon Eating, 1880 – 1980. A number of images and recipes have been omitted.

|

| Dora Engeman |

Half a century ago, when she was in her 90th year with a few more yet to go, my grandmother still cooked on a wood-fired range in the house her husband had built in 1904 near Silverton, Oregon. Grandma chopped her own kindling; she baked bread, made firm doughnuts and heavy spice cakes, whipped up apple pies and sugar cookies. She canned beans and tomatoes and corn and pears. Hot cereal—mush, or oatmeal—was the breakfast staple at grandma’s. Her fried beefsteak and boiled potatoes, green beans and stewed tomatoes were the cornerstones of both dinner (midday) and supper (in the evening). Eating at grandma’s was very different from eating at home.

I thought grandma’s cooking was repetitive and boring and staid. How had she learned to cook, as a young woman on a Minnesota farm? Had her cooking changed over the years, after she moved to Oregon? I never saw a cookbook, never saw her use a recipe, and I thought she was somehow very set in her old-fashioned ways. But I never talked to her about that. I wish I had.

Today, regional foodways is a rising area of study. It goes along with our new-found interest in locally-sourced foods, in farmers’ markets, in made-from-scratch meals, in farm-to-table restaurants, in unprocessed and minimally-processed foods, in the rediscovery of forgotten and neglected grains and vegetables, in living the life of a locavore and shunning hothouse tomatoes, in collecting heirloom seeds and heirloom chickens, in home canning and preserving—all these concerns take their cues from past practices. As we explore these paths, it can be rewarding to know more about what we really did do with our food in the past, and how that differs from what we are doing today. It can be useful to consider why ingredients and methods changed. Were these changes for the better, in the long term? or were they mere novelties, or side roads that came to a dead end? Or were they the consequence of other changes?

My own search in this field of regional food history—of Oregon foodways—has been aimed at examining questions about what ate, how we prepared it, what has changed, why it has changed, and what have been the consequences of change. In this post I’m looking at some of what I have found from studying local, regional, “community” cookbooks.

A brief setting of the stage: this post deals an Oregon where the native Indian populace has been effectively overrun and pushed aside; few of their foods or culinary practices were adopted or adapted by the new wave of immigrants, salmon being the one exception. This was an Oregon with a population, in the 1880 census, of 174,768 people; fewer than one in ten of them lived in the Portland area. The residents were overwhelmingly newcomers, from the American upper South or New England or the Atlantic states, or from northern Europe. This is a society that is newly laid out, one that has erased earlier societies and their foods and their practices, and that has brought with them not only an assortment of imported food cultures, but also the edible plants, fruits, and animals themselves to support their habits. By 1980, Oregon’s population was more than 2,633,000, and half lived in the Portland area. Still, a very large proportion were immigrants to Oregon, not native to the area.

Between 1880 and 1980, American food consumption was impacted by the development of such processes as canning, refrigeration, and freezing, by railroad transportation and express services, by highway transport. I won’t be saying much about any of this, nor of changes in processing and distribution, meat packing and flour milling, grocery stores and supermarket chains, farm consolidation and monster agribusiness.

Studying foodways requires using sources that are often unfamiliar to historians. Paper ephemera, for example: the kind of printed material that has often escaped the attention of libraries and historical societies. Menus, programs, posters, advertising leaflets, and mail-order catalogs were intended to be used for a brief time and then thrown away. Those local community cookbooks, too, were often viewed as unimportant items of daily life, and few went into libraries.

Cookbooks are one of the basic tools used by cooks, and they can give us many insights into what was being eaten and how it was being prepared. The earliest American cookbook was The Compleat Housewife by Eliza Smith, published in 1742; it’s a copy of a London publication of 1727. The first American-born cookbook was American Cookery, by Amelia Simmons, issued in 1796. By the mid-19th century, a number of cookbooks were being published in the United States, and titles such as Catherine Beecher’s Miss Beecher’s Domestic Receipt-Book (1846) were nationally distributed and widely available.

The late 19th century saw a bloom of commercially-published cookbooks, running parallel with a rising interest in cooking schools, domestic science, and women’s rights. Among these were the White House Cook Book (1888; this is the 1938 edition); Fannie Farmer’s Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (1896); and Lowney’s Cook Book, issued by a Boston chocolate company (1907).

The end of the 19th century also saw a new blossoming of cookbooks compiled by local organizations, usually only locally distributed. Most of these small cookbooks were created and sold in support of a good cause of some kind, such as disaster relief efforts, a church mission program, or to support a special school. These are often called “community” cookbooks.

***

The first of these community efforts in Oregon was the Web-Foot Cook Book, compiled and published by the San Grael Society of Portland’s First Presbyterian Church in 1885. In his 1964 book of reminiscences, Delights & Prejudices, James Beard describes the Portland of the 1880s as a “food-conscious city,” and he cites the Web-Foot Cook Book as evidence, reprinting from it the recipe for Trinity Church Salad. (While it was the Presbyterians who issued the cookbook, they rather ecumenically deigned to include at least one Episcopalian recipe.) The Web-Foot was a comprehensive cookbook, with sections on beverages, bread and biscuits, cake, candies, desserts, fish, jellies and ice creams, meat and game, pickles and sauces, pies, preserves and canned fruit, salads, soups, and vegetables. There were also sections on foods for invalids, and—an Oregon touch, for sure—foods suitable for when out camping.

Here’s a recipe from the Web-Foot, a sweet one from among the many cakes, pies, and desserts found there. Perhaps because they were often pièces de résistance in community cookbooks—show-off recipes for the contributors—desserts were often over-represented. This recipe was provided by Mrs. Martin Winch, whose husband was a temperance man; Martin Winch was also the man who later made sure that the fortune created by his uncle, Simeon Reed, was used to create Reed College rather than being distributed to wastrel family members.

A CELEBRATED TIPSY CHARLOTTE.

Given by Particular Request of Many Friends.

Take sufficient lady fingers to fill your glass dish, one pound of almonds, blanched and split, fill a bowl about two-thirds full of sherry wine—add one-third water, sweeten to taste, split the lady fingers lengthwise and dip them into the wine; arrange a layer in bottom of your dish, then a layer of almonds, and so on until your dish is nearly full. Make a custard of five eggs to a quart of milk, flavor with almond; when cold pour over your lady fingers, let stand one hour. If you can procure it whip one pint of triple cream to a stiff froth, and put on top of dish, daubing it here and there with minute triangles of currant jelly.

|

| Tipped-in recipe, Monday Club |

Another early Oregon community cookbook is the Monday Club Cook Book, issued in Astoria in 1899 by the Ladies of the Every Monday Club of Astoria’s First Presbyterian Church. This too is a cookbook that covers a range of edibles: its 138 pages include recipes for soups, fish, game and poultry, vegetables, salads, meats, breads, cakes, puddings, pies, pickles and jellies and jams, chafing dish dishes, candies and ices, plus recipes in categories labeled miscellaneous, “from the men,” and “things worth knowing.” Notable in this book are the fish recipes—also noteworthy is the fact that so many of them specify canned, not fresh, salmon, reflecting the city’s standing as the salmon canning capital of North America.

In the first two decades of the 20th century, a spate of community cookbooks were published in Oregon, most them by church groups. My own pre-1920 collection includes cookbooks from St. Matthew’s Episcopal Mission in South Portland, the Piedmont and Forbes Presbyterian Churches of Portland, Presbyterian groups in Clatskanie, North Bend, Grants Pass, and Burns, Methodists in Portland, Klamath Falls, Talent, Roseburg and Corvallis, Episcopalians in Astoria, and the Christian Church in Richland—among others. For good measure, there are cookbooks from the Alpha Club of Baker City and the Women of Woodcraft in La Grande, but Protestant women’s groups were the most prolific producers of them.

* * *

Those first decades of the 20th century also saw the birth of three more widely-significant Oregon cookbooks. Two were fund-raising community cookbooks, while one was a community-based effort to “make the world safe for democracy.”

The Neighborhood Cook Book was published in 1912 by the Portland section of the National Council of Jewish Women. It was a fund-raising effort for Neighborhood House, a settlement house established in 1905 to aid immigrants find a place in their new community. It was exceedingly popular; a second edition was issued in 1914, and a third in 1932. The Neighborhood Cook Book is distinguished by its ecumenical range. There is an entire section on shellfish, and two of the recipes in the 1912 edition represent the earliest cookbook versions I have found of a once-famous West Coast dish, crab Louis.

The Portland Woman’s Exchange Cook Book came out in 1913, a fund-raiser for the Portland branch of a group that endeavored to help women find a remunerative outlet for such “womanly” skills as baking and cooking, candy-making and sewing, textile crafts and china painting. In Portland, the group ran a tea shop for many years. The cookbook, with its recipes contributed by supporters of the Exchange, became legendary. It was republished in 1973 and again in 1987 by the Oregon Historical Society, with an introduction and notes by James A. Beard, who by that time was himself a Portland legend, and Portland was a city of rising culinary fame.

|

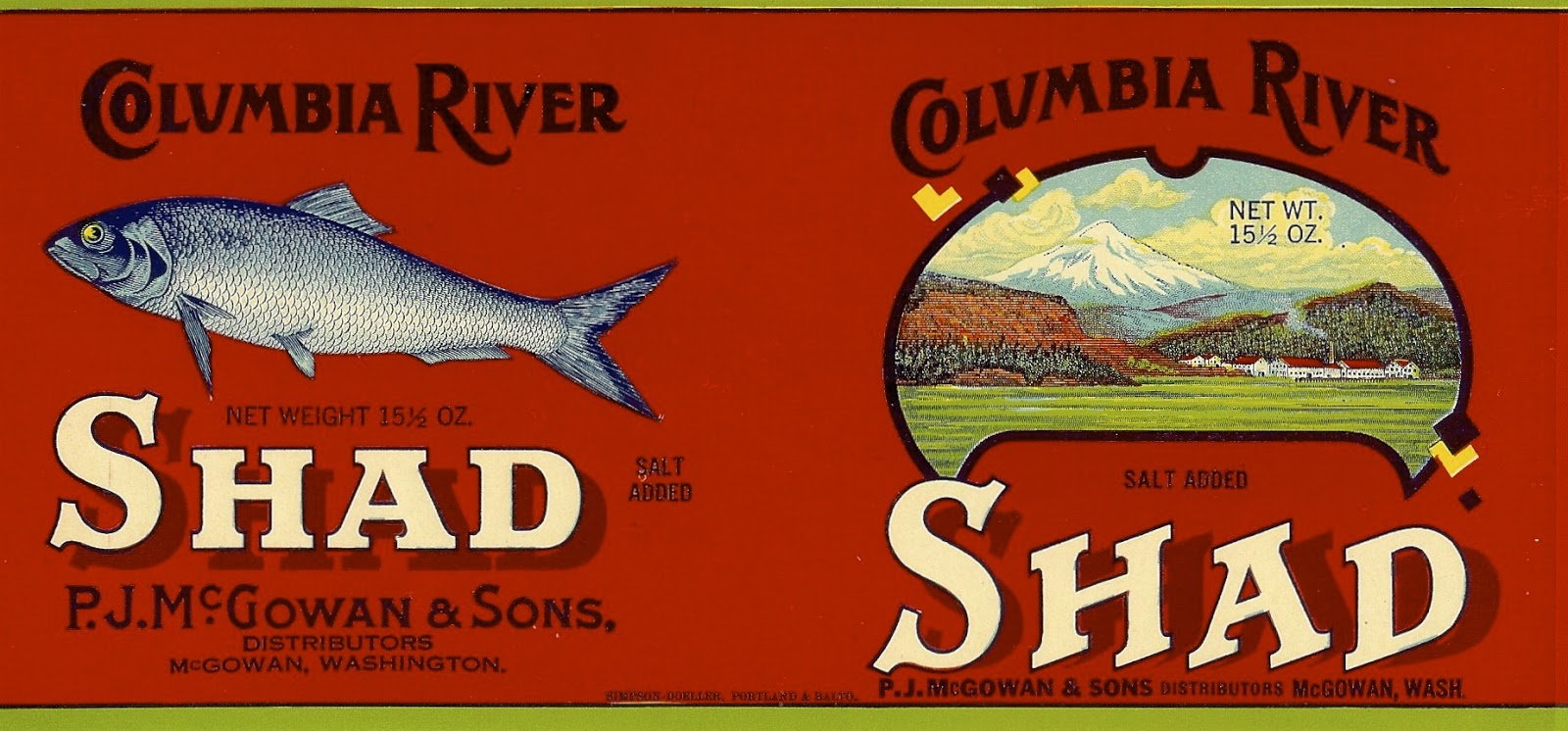

| Label for canned shad |

Beard makes note of “a perfectly delicious recipe for baked shad and another for broiled shad with an herbed sauce”; in all, there are seven recipes that feature shad, and but four that feature salmon (one specifying canned salmon). That points out the oft-changing fortunes of our fisheries: shad are not native to the Pacific coast, having been planted in the Sacramento River in 1871 and appearing in the Columbia by the 1880s. Today, shad are “the signature fish of the modern Columbia River,” according to the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, vastly outnumbering salmon. But our use of shad as a food fish has declined near to the vanishing point, despite their abundance and edibility.

An All-Western Conservation Cook Book; Containing all the Tables, Recipes and Important Items Discussed in Aunt Prudence’s Kitchen Department of the Evening Telegram, also titled the Telegram Conservation Cook Book, was a product of World War I. Published by the Portland Evening Telegram in 1917, it was compiled by Inie Gage Chapel—Aunt Prudence—from recipes sent in by readers responding to the newspaper’s efforts to conserve food during wartime.

One of the notable features of the book is the effort to account for all the costs of putting a dish on the table, down to the 1/100th of a cent, and including fuel costs (manufactured gas, electric, or wood). The emphasis that Aunt Prudence puts on home-grown fruits and vegetables in the Telegram cookbook was later apparent in the column that she wrote for the Oregonian from 1919 to 1921, “Chats With Home Gardeners.” Herbert Hoover, who headed wartime food conservation efforts, strongly promoted fish as an alternative to meat—Aunt Prudence also pushed this, but she cautioned that despite its availability, fish was often expensive. While salmon is exalted in this cookbook, shad is neglected.

But crappie has a small place in a notable “war holiday dinner menu” from Mrs. W. W. Williams “in which each and every item of each and every recipe in the whole menu meets Mr. Hoover’s requests of us.” Mrs. Williams’ dinner for six costed out at $2.5545, or less than 43 cents per person.

The post-World War I era brought a proliferation of community cookbooks in Oregon. While the Protestants still led the cookbook parade, now there came offerings from the likes of Catholics and Seventh-Day Adventists as well. Oregon’s vegetarian Adventists apparently created Yeatum, a versatile meat substitute that has disappeared without a trace—the only entry I could find on Google was my own blogsite.

|

| Mrs. Williams’ war holiday dinner |

In the 1920s and 1930s there are cookbooks compiled by Masonic lodges, the ever-supportive University of Oregon mothers, the Oregon State Grange, and improvement groups like the Reedsport Community Club and the Dallas Woman’s Club (Prune City Cook Book, 1926). The Dallas effort has a number of prune recipes that deserve a revival.

The inter-war decades also saw several commercial cookbook publication efforts. Most notable of these was Mary Cullen’s Cook Book (1938). This was a different kind of “community” cookbook, not one created to fund a charitable cause. Mary Cullen was the fictional figurehead of the “household arts” (read: women’s) department of the Oregon Journal newspaper of Portland. Most of the community cookbooks I’ve described were compiled from recipes sent in by members of the community, and their names were usually attached to them. Newspapers had long published individual contributed recipes, and they, too, frequently named the contributors.

But when a big-city newspaper like the Journal went to the effort to put together a general, comprehensive cookbook for the Oregon homemaker, the only name shown was that of the imaginary Mary Cullen, and the proceeds from the book benefitted the publisher. One feature of the book was a section called “Oregon Favorites,” with recipes that featured local foods such as smoked sturgeon, loganberries, elderberries, huckleberries, razor clams (clamburgers!), apples, venison, salmon, and prunes.

A post-World War II version was published in 1946 as Mary Cullen’s Northwest Cook Book, edited by the very real Catherine C. Laughton, “director, Mary Cullen’s Cottage, Household Arts Service of the Oregon Journal.” While there was no longer a section called “Oregon Favorites,” most of the recipes, including clamburgers, survived the war. Two new sections appeared: foreign foods, and outdoor cookery, campfire and backyard barbecue menus.

While many community cookbooks included recipes that made a nod toward “foreign” foods—chop suey, tamale pies, and spaghetti with tomato sauce, baked, being common contributions—the 1946 Mary Cullen cookbook did spread its wings a bit further, with sukiyaki (despite the war) and sarma, Syrian stuffed cabbage among the entries. The chicken curry recipe is headed by the note, “Curries in the Pacific Northwest were mainly confined to a simple lamb stew or leftover lamb roast flavored with curry gravy until World War II veterans returned. Now chicken curry is a demanded dish.” And this recipe involves a lot more than just curry gravy.

|

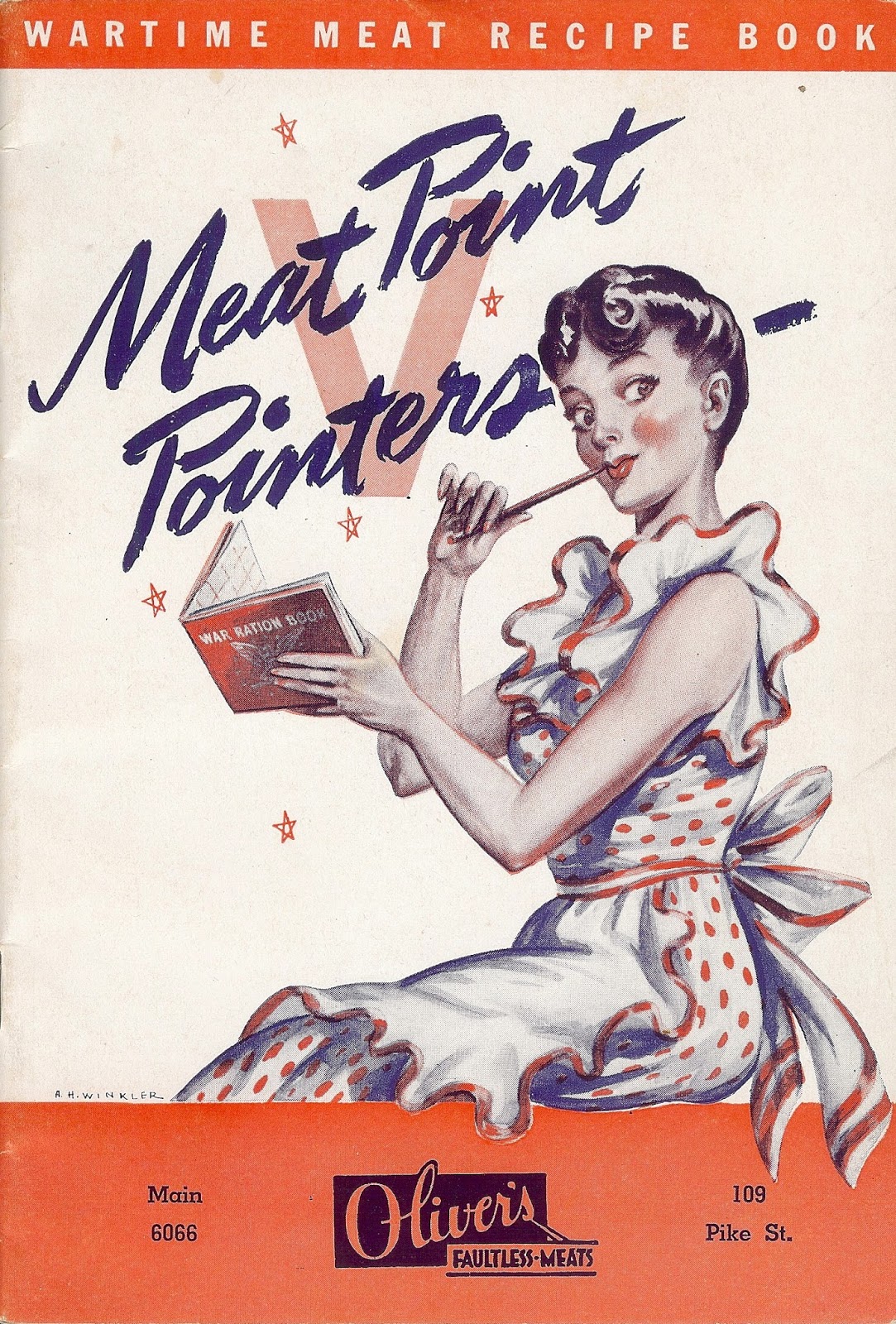

| Seattle, but they were everywhere! |

World War II again brought food rationing and food conservation efforts, on a wider scale, and for a much longer time, than did the first war. In the aftermath of the war there was not only a wider spread of interest in foods from foreign lands, but also a recommitment to some old standards. Supplying beef to the armed forces, for example, had led to the near-disappearance of beef from home and restaurant tables, and the years of shortage raised beef to new heights afterward.

Outdoor cooking—barbecuing—was well suited to post-war suburban life, and beef steaks and hamburger sandwiches celebrated the return of cow meat. Commercial cookbooks, produced for a national market by meat packers and other producers as well as mainstream publishers, fed this interest. So did cookbooks produced by regional publishers such as Sunset Magazine, and booklets from Pacific Northwest providers of beef, buns, and condiments.

The postwar years also saw other expressions of regionalism beyond the Mary Cullen cookbook. From national publisher Alfred A. Knopf came the very influential West Coast Cook Book (1952) by Helen Evans Brown, a close friend and colleague of James Beard. Brown noted that “the recipes are the regional ones of the three Pacific states—California, Oregon, and Washington. . .” She used recipes from three different traditions: those of the early settlers, those requiring foods typical of the Pacific slope, and those developed by West Coast cooks who discovered “some new way to serve some old familiar food.”

James Beard helped bring attention to Oregon foodways in two books, his autobiography-with-recipes Delights and Prejudices (1964), which included many recipes as well as tales of his culinary youth in Portland and Gearhart-by-the-Sea, and his magisterial cookbook, American Cookery (1972), with its dozens of references to Oregon crabs and Oregon berries.

Local, community cookbooks continued to be very popular in Oregon. However, their impact appeared to decrease as the population expanded and diversified, as church-going declined, and as a market developed for more substantial cookbooks that still had a regional focus. Community fund-raising raised its bar, so to speak.

In 1954, the Portland chapter of the national Junior League service organization issued Cooked to Taste. The Junior League had begun publishing regional cookbooks to raise funds in 1929. Both the Portland and Eugene chapters have issued regionally popular cookbooks since that first one in 1954.

Beyond the boost that World War II gave to ethnic foods in community cookbooks, but the descendants of immigrants to Oregon began to look at their family background. That interest resulted in community cookbooks representing Scandinavian, German, Irish, Greek, Welsh, Japanese, and Native American traditions. There is also a proliferation of cookbooks for particular Oregon products, from beef and seafood to filberts and potatoes—some of these were community fund-raising books, some were commercial endeavors, while others were put out by commodity producers.

I’ll end this look at community cookbooks with A Taste of Oregon, published by the Eugene Junior League in 1980. It’s become a classic. The title suggests a regional approach to the recipes that are gathered in the book, and a focus on foodstuffs grown in Oregon. Today, those two impulses are driving forces in the story of Oregon foodways—but they are not yet strong in A Taste of Oregon. But the impulses grow, and grow, in the years since 1980—another story.

* * *

|

| From grandma’s arithmetical cookbook |

Going back to the beginning of this post …. Grandma died in 1968. Not until after the stay-at-home son died in 1994 did I find Grandma’s cook book. It’s a single volume: The Progressive Commercial Arithmetic for Commercial Schools, High Schools and Academies, by Wallace Hugh Whigam and Samuel Horatio Goodyear and published in many editions between the 1890s and at least 1909. Grandma’s book is stuffed with newspaper and magazine clippings and advertising fliers and leaflets and handwritten recipes from neighbors and kin, pasted on the pages, crammed between the pages.

So it became apparent that for many decades Grandma had been keenly interested in different ways to prepare food, in knowing about unfamiliar foods, in trying new products and preparations. For seven decades she had collected and winnowed a blizzard of paper information about foodways. She built her own community cookbook. Like those of the community cookbooks—and the commercial ones as well—grandma’s recipes probably reflect desires and hopes and plans as much as—more than!—what was really put on the table.

What have I learned from this? Here are some observations.

We loved oysters. Supper, dinner, lunch, breakfast. Not so much now. Not at all. And oysters have changed: another story, one I keep promising to tell.

Chicken was most often found in recipes for stews and stock, thus using up an old hen, or roasted as a special Sunday dinner event. Chicken was not an everyday meal base. Chickens were expensive. Need cheap? Have some canned salmon, make a salmon loaf.

Pies were the famous American dessert, and fruit and berry pies were and are Oregon staples. However, for fancy one-upswomanship, cakes provide a better medium for elaboration and fancy twists, at least until cake mixes took the stage. By 1980, showing off in community cookbooks was more commonly found in main dishes than in desserts.

Oregon recipes are rather sparing in the use of spices and, especially, herbs. Garlic is sometimes seen, but is used gingerly. While pickling and preserving and sausage-making are practices that use a lot of herbs and spices, recipes for them decline considerably over the century. Perhaps surprisingly, paprika and chili powder are fairly common condiments from the 19th century into the 1920s.

Vegetables are to be boiled. While the use of raw vegetables in salads increases over the years, the variety of vegetables is fairly small. And while potatoes might be thrown in with a beef roast, there is nothing seen about roasting cauliflower or beets; steaming is also rarely called for; ditto sautéing. White sauce is good.

While the variety of fruits and vegetables is considerably wider today, it is sometimes surprising what was available in Oregon in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Even then we were importing oranges and lemons, pineapple from Hawaii, bananas, olives and olive oil from Greece and Italy.

With refrigerated railcars, Oregon reaped much of the rapidly-increasing California food bounty. Oregon also took a lot of cooking tips from California, thanks to the wide circulation there of the Bay-area-based Sunset Magazine, from the 1920s onward.

Gelatine is a handy culinary ingredient. It becomes handier as home refrigeration becomes common, and as Jello introduces flavored gelatin. As has been often reported, this gelatinizing got out of hand in the 1920s and 1930s, but retreated to sanity by the 1960s.

Canned soup: cream of mushroom, cream of celery. With the casserole concept that emerged in the 1910s and 1920s, cream condensed soups became new ingredients. They are still prominent in the 1980 Junior League cookbook A Taste of Oregon.

Is there an Oregon cuisine, or a Pacific Northwest cuisine? It would appear not. What does appear, and it’s a small thread that does grow constantly thicker over the century, is that there are ingredients that are characteristic of the state and the region: salmon and crab, razor clams, venison and elk, prunes and apples and pears, huckleberries, raspberries, blackberries, loganberries, berry-berries, etc.

Little bits of paper—pages from books, clippings in scrapbooks, scrawled cards in a box—help build a larger picture of Oregon foodways. They don’t give us the whole picture, of course; there are many other areas of research for a comprehensive look at Oregon foodways. But they do provide a fascinating, wide-ranging, eye-opening viewpoint.