A Mess of Piddocks, or, Rock Oysters on Parade

“No banquet is considered complete without oysters in our modern life, and here is a delicacy that surpasses the oyster, but that cannot be shipped.”

|

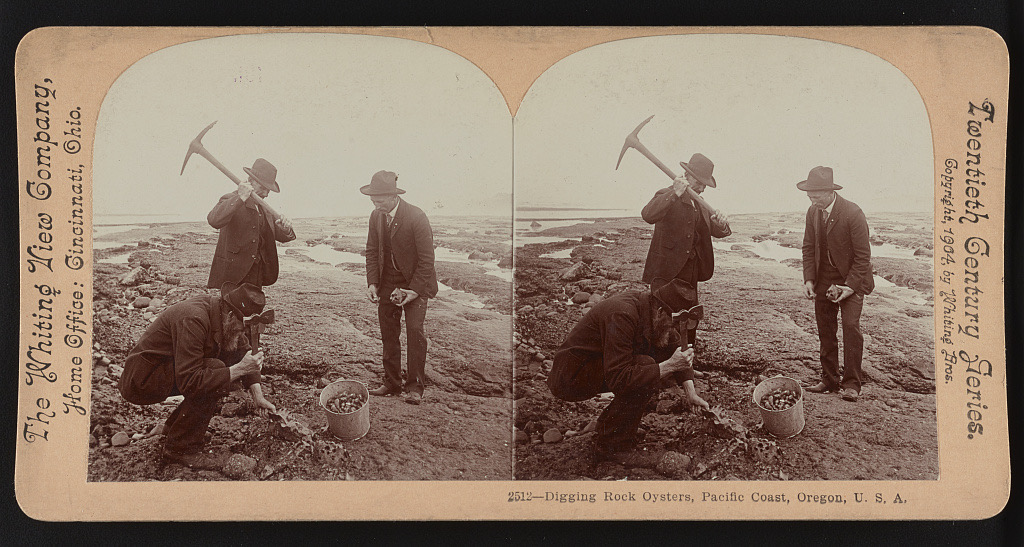

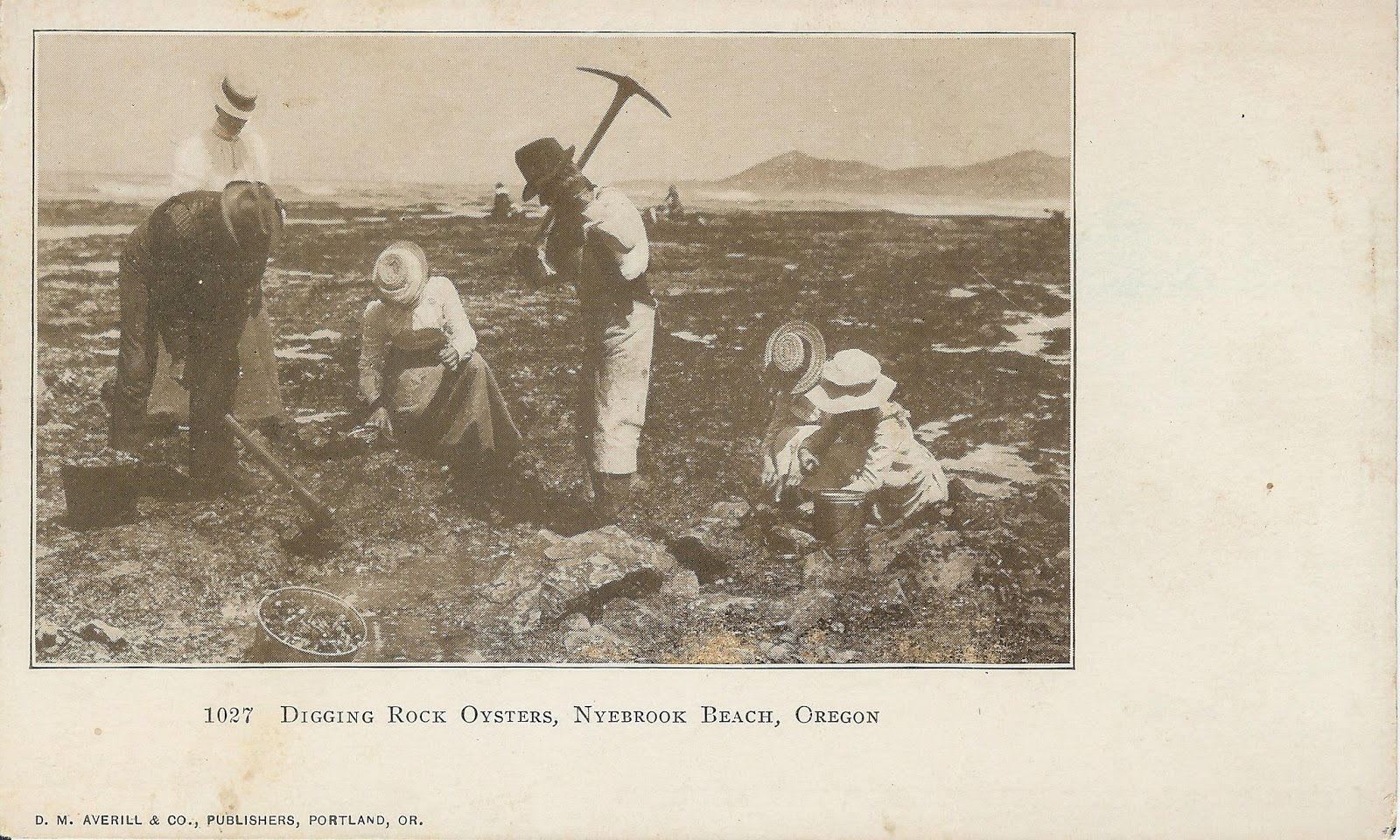

| Postcard view, Nye Beach, Newport, Yaquina Head in background |

An exemplary bibliographer and city planner of my acquaintance, Nicholas Starin, asked me an unexpected question. Namely, “What do you know about the culinary use of piddock clams in the Pacific Northwest?”

Piddocks, or rough piddocks, rock oysters, Zirfaea pilsbryi or a variant thereof, or boring clams: they are clever creatures that can bore into mud, or clay, or sandstone, or soft rock. They are eminently edible, and varieties of piddocks are found all along the North Pacific coast. But it appears that the soft rocky reefs near Yaquina Bay were once very popular places to gather ’em and eat ‘em in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Because after they are removed from their rocky burrows, they die, they are the kind of prey that you eat right away: they don’t travel. They’ve never appeared on restaurant menus. Well, rarely.

| Looking north toward Nye Beach and Yaquina Head |

I’ve been poking into the history of their consumption in Oregon off and on for a long time, without a great deal to show for the effort. My mother grew up in Toledo in the 1920s and early 1930s, and she talked of occasionally finding some rock oysters around Agate Beach and Newport, but she said they had pretty much disappeared by about 1940. I remember finding a few as a kid (which had occasioned my mother’s remarks), but we didn’t dig them out and I’ve never eaten one. Nor have I seen a recipe that specifically calls for them, but then “clams” can encompasses a lot, so clam recipes were no doubt applied to rock oysters.

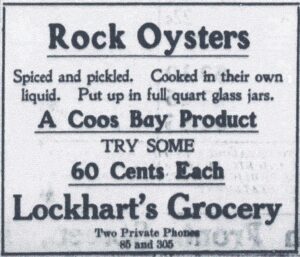

In the booklet Edible? Incredible! (by Marjorie Furlong and Virginia Pill; published 1973 in Tacoma), the authors say of the piddock, “It bores into shale and clay; therefore in order to extract these clams, much beach rock must be destroyed by digging a large hole. Since the piddock is no more flavorful than any other clam, avoid taking these species when it is possible to gather other kinds.” Of course, if no others are around, hack away, and so the seashore sojourners did, ultimately destroying virtually all of their accessible habitat. Rock oysters still exist, of course, but on rocky offshore reefs and outcroppings. Rock oysters were also to be found in the Coos Bay area, and in 1913 a real estate agent alleged that they were common at Yachats, but that appears to have been a flat-out lie.

Annie Ditallo. Lincoln County Historical Society

According to an article in the Oregonian on November 7, 1920, “it is necessary to have special equipment. Many of the devotees… carry sledges and regular rock drills with them on their vacation trips… .” Needless to say, the rock oysters “are getting scarcer every year.” I did find that, despite their perishability, they appeared on the menus of a few hotel dining rooms, at least in the Newport area. Annie Ditallo, a local Indian forager, was known as the “rock oyster queen” and supplied the delicacy to hotel chefs. When president William Howard Taft visited Portland in 1909, Newport rock oysters were served to him at an all-Oregon banquet, where they “made a hit with the president” according to an article in the Oregonian of August 29, 1922. That is the only account I can find of fresh rock oysters making it to a Willamette Valley table.

Daily Capital Journal, Salem, April 5, 1909. Ad for Bloomer’s Addition

Coos Bay Times, Marshfield, June 22, 1911

Cultural Images