Mid-Valley Potatoes

With meat-and-potatoes being the default basic American meal, it’s not surprising that potatoes are a major crop across the nation. Maine, Washington, and Idaho are famous for them. Notable production areas in Oregon today are the northeastern and far eastern parts of the state, the Klamath Basin, and the Deschutes country. And while many crops are raised in the Willamette Valley, no renown is attached to the potatoes grown there. Not that some people didn’t try to change that. Two notable efforts are exhibited by these bits of ephemera from an area with the mundane moniker Mid-Valley.

With meat-and-potatoes being the default basic American meal, it’s not surprising that potatoes are a major crop across the nation. Maine, Washington, and Idaho are famous for them. Notable production areas in Oregon today are the northeastern and far eastern parts of the state, the Klamath Basin, and the Deschutes country. And while many crops are raised in the Willamette Valley, no renown is attached to the potatoes grown there. Not that some people didn’t try to change that. Two notable efforts are exhibited by these bits of ephemera from an area with the mundane moniker Mid-Valley.

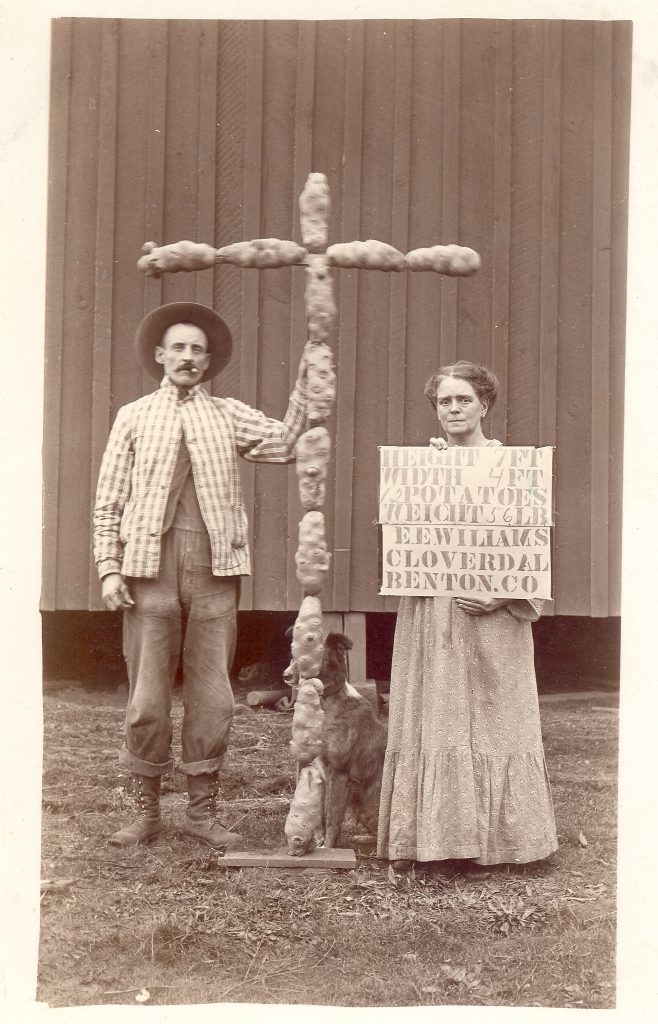

First is this remarkable photograph of a potato cross, made of a dozen very large and very lumpy tubers, and exhibited with a farming couple and their dog (half-hidden by the base of the cross). The sign says that the cross is 7 feet high and 4 feet wide, the 12 potatoes weigh a total of 56 pounds, and that they were grown by E. E. Williams of Cloverdale in Benton County.

The image was part of a collection of photographs taken by William F. Peacock (1845-1909), a prominent farmer and amateur photographer of North Albany, Benton County, Oregon. An initial search failed to pinpoint a place in Benton County called Cloverdale, so I reluctantly concluded that this was not an Oregon photo.

I was wrong, as additional research revealed. Lo and behold, the same photograph appeared in the Portland Oregon Journal newspaper on December 25, 1911, under the caption BENTON COUNTY SPUDS SHOW UNUSUAL GROWTH. The story contains no more information than is shown in the photograph, save for the line that E. E. Williams “has been engaged in potato culture in the Cloverdale area for a number of years.” Also, “One of the spuds measured 14 inches in length.” Keep in mind that in 1909, the Northern Pacific Railroad had introduced the “Great Big Baked Potato” on its dining cars: these were not freaky potatoes, they were just supersized. And were now, perhaps Irish Catholic!

Harrisburg cookbook

The second piece of potato ephemera is a small cookbook published in 1912 by the Ladies Auxiliary of the Harrisburg Improvement Club. In 1911, the Harrisburg Potato Carnival was inaugurated in this small town, which is about 30 miles south of the Williams farm. For the second year of the carnival (it lasted through at least 1914), the ladies compiled a reputed 180 recipes for “King Murphyâ” (very clearly an Irish Catholic potato), including one written in verse form. There are recipes for baked potato fritters (a fried dessert with brandy, sugar and lemon), potato soup with oysters, potato doughnuts, and Saratoga chips, now known as potato chips.

An online newspaper search for Mid-Valley potato news in the 1900-1920 period makes it clear that while potatoes were not a regional feature crop, they were widely and profitably grown. (This is a period when Salem boasted of its cherries, Dallas about its plums, and Lebanon of its strawberries.) Railroad boxcars full of Linn County potatoes were shipped to northern California markets; for example, in 1901 W. H. Hogan sent 14 carloads south from Albany.

There were other potato novelty reports as well, such as this one in the Morning Oregonian of March 27, 1914:

Sixteen hundred pounds of potatoes went through Albany by parcel post yesterday. They had been shipped from Lyons, on the Corvallis & Eastern [Railroad], 28 miles east of Albany, to Fort Rock, in Southern Oregon. The potatoes were in 48-pound sacks.

Parcel post was a new service of the postal system, beginning January 1, 1913. Parcels could weigh no more than fifty pounds, but the low rates and the nationwide service immediately pushed the growth of mail order business (notably Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward), sometimes, as in this example, to extremes. Those 34 sacks of potatoes went by train in the US mail from Lyons to Albany to Portland to Wishram (Washington) to Bend, and then via horse or auto stage to Fort Rock, a journey of almost 350 miles.

And here, from the Potato Cook Book, is your poetic recipe for potatoes prepared in a hobo jungle along the railroad tracks.